- #StopSwappingAir - February 20, 2021

- Why I fled - September 15, 2020

- 5 years later: Ebola outbreak shows continued weaknesses of global response - June 23, 2019

(This is a reprint and renaming of a 2015 post, regarding the largest Ebola outbreak ever, beginning in West Africa in 2013-2014. In summer 2019, the world had its second-largest outbreak. Widespread transmission crossed borders from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Uganda. Although there is some vaccine available, an ongoing civil war and fear-related violence against clinical and immunization workers have rendered delivery of vaccine difficult. WHO has decided 3 times to decline calling this outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, a PHEIC. For further context regarding International Health Regulations, read on. Note: This outbreak was finally declared at PHEIC on July 17, 2019.)

One year ago this month, the United States was fully in the throes of terror about Ebola. Thomas Eric Duncan had arrived from Liberia in September 2014 and died in a Dallas hospital on October 8, 2014. News coverage from West Africa showed healthcare workers in full isolation garb, overflowing hospitals and bodies in the streets. Continuous transmission was ongoing in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, with warnings of exponential increase. To date, over 28,000 cases have affected Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia with over 11,000 deaths; 36 cases have affected 7 other countries.

History of the Outbreak

Public health officials have determined that the outbreak probably began in Guinea in December 2013, when an 18 month-old in Meliandou, Guinea was infected, possibly by a bat. The outbreak circulated within and outside that community, misdiagnosed as cholera and Lassa for about 3 months. The previous outbreaks of Ebola had been in Central Africa, so West Africa lacked expertise with Ebola. By February 1, 2014, ill family members had gone to hospitals in the Guinean cities of Gueckedou and Conakry, infecting healthcare workers in densely populated urban areas and launching numerous transmission chains throughout Guinea.

In March 2014, Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF, aka. Doctors Without Borders), the Guinean government and the World Health Organization (WHO) first became aware of confirmed Ebola cases near an MSF facility in Guinea. MSF had responded to numerous Ebola outbreaks in Africa and had extensive expertise. By the end of March 2014, MSF was warning of “unprecedented” spread of this Ebola outbreak, declaring an emergency. Meanwhile, WHO denied that a true epidemic emergency existed. By June 2014, MSF would be so overwhelmed that it could no longer treat all of its patients. It would be August 2014 before WHO declared a Level 3 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and a full international response was mobilized.

The International Health Regulations (IHR), 2005 revision

2015 marks the 10 year anniversary of the revised treaty known as the International Health Regulations (IHR). Developed after the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory (SARS) outbreak and implemented in 2007, the IHR were designed to help identify infectious disease threats and prevent global spread while also minimizing impediments to travel and trade. In 2003, SARS emerged and spread to 37 countries, fueled in part by China’s denials of an outbreak. 196 countries, including all World Health Organization (WHO) member states are signatories of the IHR treaty. By the end of 2014, less than 1/3 of the signatories had met the minimum capabilities of the IHR, requirements that were supposed to have been met by the end of 2009.

According to WHO, at the start of the outbreak in the 3 most affected countries, there were approximately 2 doctors per 100,000 people. There was no laboratory testing readily available. Transportation and communication infrastructures were inadequate, infection control protocols and isolation units were non-existent, and there was deep and often violent distrust of healthcare workers and of the governments involved. The abilities of the governments and outside agencies to prevent, detect and respond to communicable disease outbreaks in this context proved highly challenging and showed deep rifts in how various countries have (or have not) addressed the IHR.

In a September 2015 address to an Ebola workshop at the Institute of Medicine in London, WHO Director-General Dr. Margaret Chan said,

“A key objective when revising the IHR was to move away from a passive approach to controlling epidemic spread at borders to a proactive approach that could detect an event early and contain it, before it had a chance to spread internationally.

That objective was justified, as WHO and its partners had contained hundreds of outbreaks, also of Ebola, at source, with little or no international spread, for more than a decade.

However, as we have learned, this proactive approach works only when countries have core capacities for early detection, timely notification, and response in place.”

Dr. Chan has identified three main weaknesses to date in the performance of the IHR:

- Compliance with building core capacities in detection and response by the member states has been “dismal” with countries often making it the sole responsibility of ministries of health, with little engagement by other relevant ministries such as finance, trade, tourism, agriculture and animal health.

- Many countries went beyond WHO recommendations, such as placing restrictions on travel and trade that further isolated very poor countries in need of medical assistance, food and fuel. WHO does not have a mechanism for enforcing compliance with their recommendations.

- There is no formal alert level aside from a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). This would require an amendment to the international treaty, which can take several years.

The Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA)

September 7-9, 2015 in Seoul, the Republic of Korea hosted senior officials of 47 governments, 9 international organizations and a dozen NGOs at the 2015 Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) High-Level Meeting in Seoul. GHSA actions are an attempt to close logistical gaps in implementing the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), specifically the IHR treaty. The Seoul meeting was the fifth GHSA meeting since Feb 2014, and the first since the much-publicized delayed international response to Ebola in West Africa.

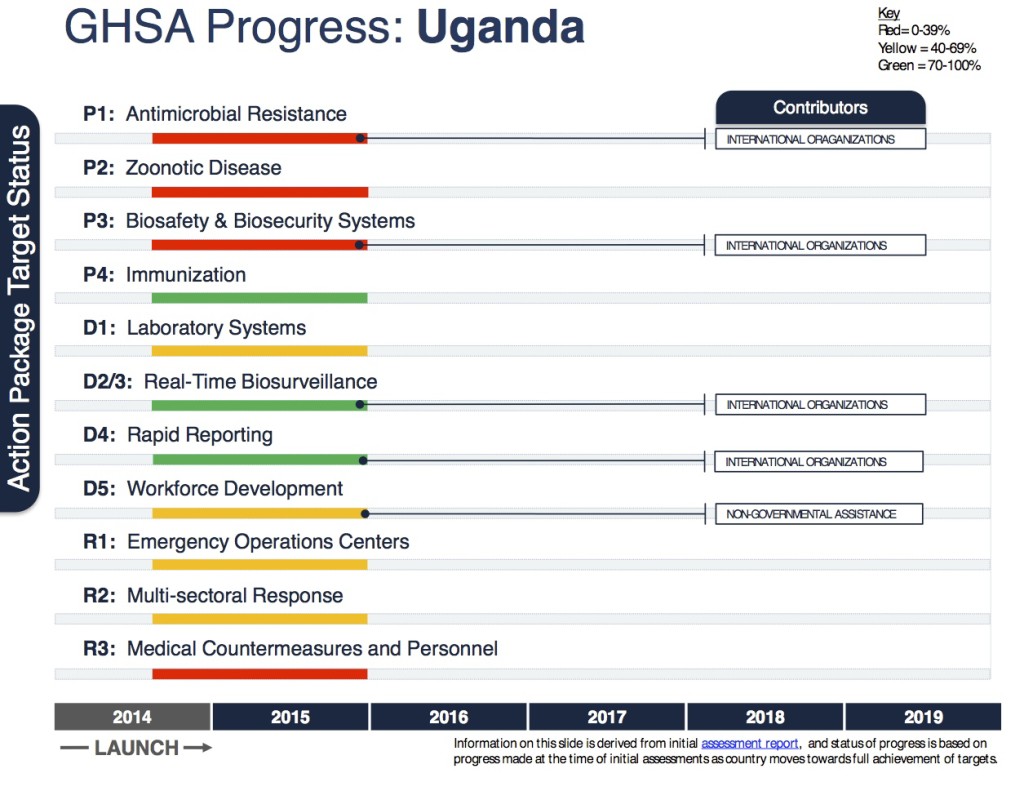

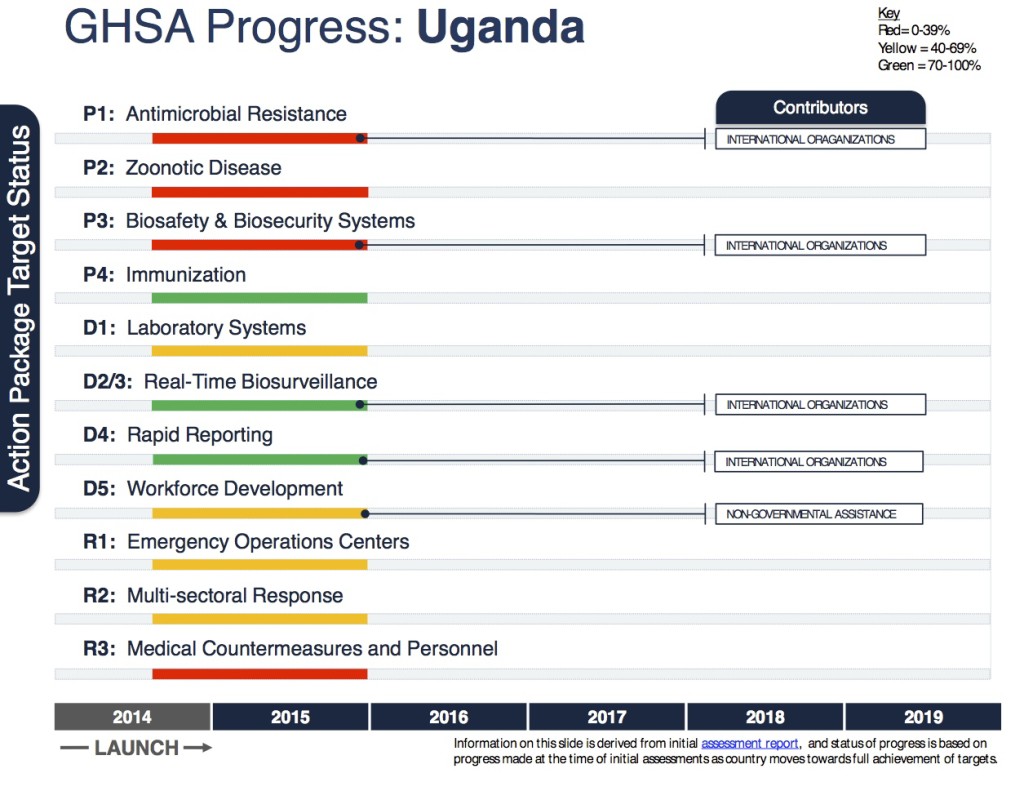

Because the IHR is a legally-binding international treaty, it is very difficult to change, but some states can offer assistance to others in meeting the goals of the IHR by helping countries to meet measurable objective outcomes. The GHSA working groups help member countries to identify gaps and to meet the regulations of agreed-upon global health security frameworks. These outcome areas are found in GHSA “Action Packages”, which divide Prevention, Detection and Response capabilities into 11 areas.

- Prevent 1: Antimicrobial Resistance

- Prevent 2: Zoonotic Disease

- Prevent 3: Biosafety and Biosecurity

- Prevent 4: Immunization

- Detect 1: National Laboratory System

- Detect 2 & 3: Real-Time Surveillance

- Detect 4: GHSA Reporting

- Detect 5: Workforce Development

- Respond 1: Emergency Operations Centers

- Respond 2: Linking Public Health with Law and Multisectoral Rapid Response

For example:

More Pilot Assessments can be seen here.

The US has pledged $1 billion to help bridge the gaps in 17 partner countries: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Uganda as well as Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Vietnam. In each of these countries, there is a 5-year roadmap to achieve and sustain each of the GHSA targets. At the 2015 G-7 Summit in Germany, G-7 leaders pledged to collectively assist at least 60 countries.

What about the World Health Organization?

Up until now, WHO has lacked any regulatory authority and is a consulting body that lacks clinical front-line staff. Its annual budget of $3.98 billion is insufficient to meet the expectations upon it. (The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention budget for the same period was $6.8 billion.) 80% of WHO’s budget is earmarked to specific programs. They lack resources and surge capacity to respond to emergencies. WHO can advise but not interfere with the policy decisions of sovereign nations.

In speaking to the Opening Remarks at the Review Committee on the Role of the International Health Regulations in the Ebola Outbreak and Response in August 2015, Dr. Chan discussed ways in which the response has been found to be inadequate, asking the Review Committee for recommendations. “We need to put in place corrective strategies just as quickly as possible,” she stated. “The IHR is a principal instrument for doing so…If its legally-binding obligations on States Parties are not being met, change is urgently needed. If WHO is not exercising its full authority under the regulations, change is urgently needed.”

Lessons from Ebola

CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden told the CDC Grand Rounds about Ebola last month that there were 3 main lessons that we should take away from this Ebola outbreak:

- Countries need to be prepared on an individual level to detect and respond to disease threats.

- The international community needs to be ready and willing to step in with an international surge capacity to respond if the country in question is overwhelmed.

- We need to increase awareness and training in Infection Control, for the safety of patients and healthcare workers. Healthcare facilities are always in a unique position to either contain or amplify disease.

In many ways, the international community has dodged a bullet with Ebola virus. Despite the extensive and frightening news coverage of Ebola, it is not very contagious. It is not as easily transmitted as measles, influenza, smallpox or SARS. Unlike those diseases, Ebola is not airborne, and contagious people are showing symptoms by the time they are infectious.

There will be a next time. Ebola has devastated lives and economies in West Africa. WHO, the CDC and the GHSA groups are trying to utilize the lessons and international concern generated by the Ebola outbreak to make needed changes. Hopefully, helping to bring the other 2/3 of WHO member nations into compliance with the International Health Regulations will leave us all better situated to recognize and respond to epidemic threats.

Links:

Timeline of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa 2014-2015

MSF’s Special Briefing on Ebola to the United Nations. September 2, 2014.

Timeline of the WHO response to Ebola in West Africa, 2014-2015

Weaknesses of the IHR, per WHO Director-General Chan

NPR story: WHO’s perceived failures during the West African Ebola crisis

November 2015 Emerging Infectious Diseases article: CDC role in the Ebola outbreak